How Maths Anxiety Spreads: What We Learned from Others

This is the fourth post in our blog series, When Maths Triggers Anxiety. If you’re new here, we encourage you to start with the first post. You can explore the full series here.

Maths anxiety is not only an individual experience, it is also a social phenomenon. Just as children acquire language, habits, and social norms by observing others, they can also pick up fear and apprehension around mathematics. Understanding how maths anxiety spreads helps parents identify subtle influences and respond in ways that foster curiosity and confidence rather than worry and avoidance.

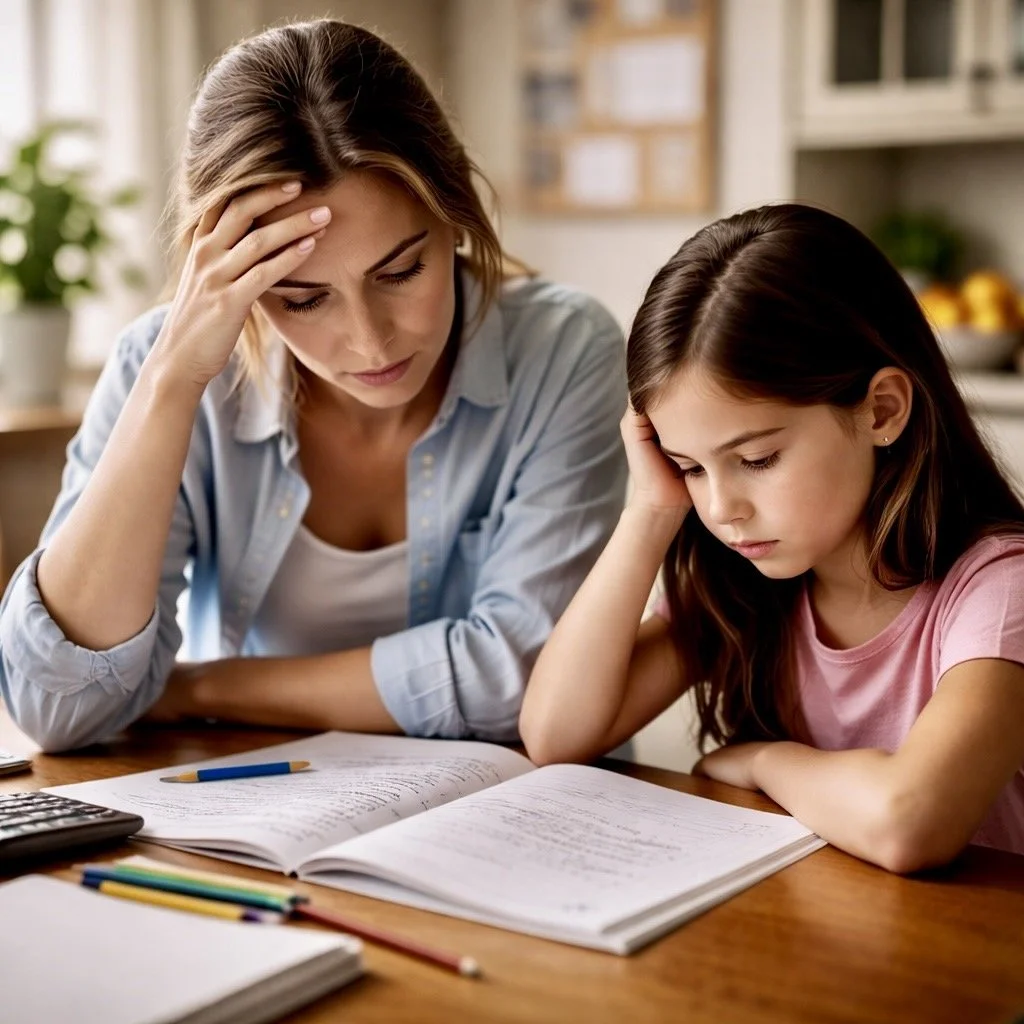

Modelling by adults

Children are highly attuned to the behaviours and emotions of adults in their lives. Parents, caregivers, and teachers model reactions to maths through both words and actions. A parent who sighs when opening a maths workbook, avoids discussing numbers, or expresses self-deprecating statements like “I was never good at maths” is inadvertently signalling that maths is threatening or unpleasant. Teachers who rush through explanations, show visible frustration, or apologise before teaching maths can similarly transmit these feelings. Modelling is powerful: children often internalise these cues as truths about their own abilities long before they fully understand the concepts themselves.

Emotional contagion

Beyond explicit statements or behaviours, children can absorb the emotions of those around them. Emotional contagion is the process by which one person’s feelings are unconsciously mirrored by another. If a parent or teacher exhibits tension, stress, or dread when confronting maths, children often mirror these physiological and emotional responses, associating mathematics with fear or discomfort. This transmission is subtle but persistent, creating a feedback loop where the adult’s anxiety reinforces the child’s, and vice versa.

Messages about ability

The way adults talk about ability shapes how children perceive their own potential. Statements such as “I’m just not a maths person” or “You’re better at reading than maths” communicate implicit beliefs about who can succeed. Research shows that children internalise these messages, which can limit their willingness to engage with challenging material. Even well-intentioned praise or comparisons, such as highlighting a sibling’s skill in maths, can unintentionally signal that the child is less capable.

Classroom peer effects

Peer environments also contribute to the spread of maths anxiety. Children are sensitive to the attitudes and behaviours of classmates. Laughter, teasing, or expressions of frustration in response to mistakes can create a culture where fear of failure is normalised. Conversely, a classroom culture that encourages curiosity, collaboration, and resilience can buffer against anxiety. Observing peers struggle, panic, give up, or avoid engagement with maths can reinforce the perception that maths is inherently stressful or inaccessible.

Stereotype transmission

Maths anxiety is also influenced by societal stereotypes such as “girls are better at language and arts than maths” or “boys who struggle with maths are lazy or not trying.” Children learn from cultural cues that suggest who is “good” at maths. Gender stereotypes, cultural assumptions about talent, and popular narratives like jokes about maths being hard or “not for people like me” transmit messages that shape identity and self-expectation. These societal signals are internalised alongside direct modelling from adults, contributing to both anxiety and limiting beliefs about personal ability.

Intergenerational cycles

Finally, maths anxiety often moves across generations. Parents who experienced maths anxiety in their own childhood may unintentionally pass it on to their children through modelling, emotional contagion, and communicated beliefs about ability. The cycle is reinforced if children perceive the world of maths as threatening or inaccessible, replicating patterns across families. Recognising this intergenerational transmission is crucial: while maths anxiety can be persistent, awareness allows families to intervene and break the cycle, creating a more supportive learning environment for future generations.

Implications for parents

People don’t just learn maths; they learn how to feel about maths from others. Awareness of how maths anxiety spreads offers actionable insights. By noticing modelling behaviours, emotional reactions, messages about ability, and classroom or peer influences, parents can create a more positive environment around mathematics. Strategies include expressing curiosity rather than fear, normalising mistakes, highlighting effort over innate talent, and encouraging collaborative problem-solving. Small shifts in how adults engage with maths can have profound effects, helping children build confidence and resilience rather than worry and avoidance, and breaking patterns that might otherwise persist across generations.